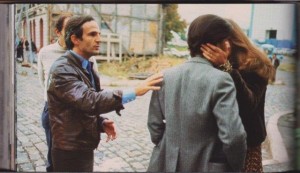

(Truffaut rehearsing kissing scene on Day for Night), still from the excellent British Film Institute

Francois Truffaut’s comic masterpiece Day for Night is mainly the story of a film shoot, but it is also an homage to film, a spoof of cliché movie-making, the problems encountered by directors when making films, the commitment of a film company to the film during an 8-week shot, the comings and goings of people during the shoot, personal lives in relation to the film’s characters’ lives, ‘film within film’, actors’ histories and relationships, time relative to film, shifts and connections between Life and Art, the beauty and mystery of women, and the process of film as compared with real life.

The famous opening scene overhead crane and tracking shot tell you this will be unlike any other film you have ever seen before. Superficially, it is just one scene extracted from a fictional film being made by Ferrand, a director (played by Truffaut himself) called Meet Pamela, of which there are only a few skeletal scenes presented, during the actual process of viewing Day for Night.

The four main actors are Alexandre, a charming old-school actor who plays the husband of Severine (Valentina Cortese), a gushy veteran French actress. Julie Baker, a beautiful American-English actress played realistically by Jacqueline Bisset, is Pamela, Alphonse’s–their son’s–played by Truffaut’s ‘look-alike’, humorous, younger ‘stand-in’, Jean-Pierre Leaud) new wife brought home to meet her husband’s parents. What follows is the cliché of the father and daughter-in-law running away together and the son’s reactions.

But Day for Night is more about what goes on behind-the-scenes of making this film within a film. And, in the process, so many likable minor characters become as interesting as the equally interesting behind-the-scenes lives of the director and principal actors. These characters include the beleaguered producer Bertrand, Joelle (the clever script girl), the cinematographer, Bernard (the beleaguered prop man), the imported English stuntman, Stacey the pregnant actress, Liliane–Alphonse’s manipulative girlfriend, the joie de vivre, soused actress Severine with her seemingly irremediable mental mistakes, Odile the good-natured hairdresser, Julie’s (the fragile main actress’s) devoted husband Dr. Nelson, and Christian, Alexandre’s (the main actor’s) surprise real-life love interest.

Truffaut also gives the viewer a glimpse into common techniques and gimmicks (such as the American day-for-night shooting filter) that create movie magic. This magic is reflected in the various delightful musical themes contributed by composer George Delerue. And this preoccupation with magic is also mirrored/linked to the “Are women magic?” question-motif pursued by the asinine Alphonse in a number of his scenes.

Indeed, there is also a special, likable, overall comic-romantic mood that accompanies the viewing of this Truffaut classic. And this mood is anchored by the third night-dream sequence in which Ferrand, as a boy, steals photo stills of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane from a movie theatre–an act which, for Truffaut, epitomizes the power, magic and influence of film-dream as he emulated it in this charming film.

It is, finally, though, an aesthetic balance that Truffaut creates in which, on one hand, film means everything to him (“Movies are always more important than Life”), while the real-life goings-on of the shoot are more interesting, dramatic, humorous, and magical, ironically, than any scene in Meet Pamela. Nowhere is this more obvious than in moments such as the absurdly hilarious “Cue the cat” sequence, or in selected actor remarks such as “It is a strange life we lead” , “No one’s personal life runs smoothly”, or “Life is more important than movies.”

We film aficionados are truly lucky that Truffaut loved movies so passionately, giving us this much inside information about his craft and art, while still recognizing that it was Life that ultimately contributes to film’s subject matter, and that Life is far more personal, deeply affecting, and significant in the long run than any film, even the great ones like Day for Night.