As powerful as the desire and drive for peace and civilized experiences are those for The Wild in its many shapes and forms, ranging from gardening to free, intense living and uninhibited natural behaviors.

For many urban dwellers, this desire and drive can be seen in the weekend and vacation getaways, often to the country or wilder locations such as the sea and mountains. The reason many folks own pets is to have that sense of The Wild in their own living rooms with a comfortable/comforting proximity. Dogs represent one kind of ideal of wildness with their responsiveness and interactions with humans. Cats are more ‘primal’ and untameable to varying degrees. (They are their own creatures and definitely a ‘wilder’ species except in the cases of such dogs as pit bulls and others that can lose whatever learned controls.)

Even bird followers and feeders seek that connection with The Wild, sometimes feeding chickadees by hand, for instance. And one thinks also of the frenzy generated in motorists by Rocky Mountain sheep or ducks appearing on a highway or city road.

Wild landscapes seem to evoke strong feelings and active passions in many who go hiking and climbing. Many times there are edges or extremes to these experiences such as in skydiving, hang-gliding, climbing Everest or canoeing the Nahanni. People feel most alive and reconnected with Nature in these more active encounters with The Wild, and closer to Earth, whether on land, in the water, or in the sky. The Wild in its physical exterior forms, then, is an insatiable, recurring part of human experience and desire.

But there are other forms of The Wild as represented by human nature, behaviors and passions. Ofttimes these behaviors ‘break out of the conventional’ to express and fulfill themselves. Something there is, as mentioned above, that wants excitement, drama, depth, and connection with wilder manifestations of human possibilities of experience.

Some of the most interesting forms and variants of The Wild are to be found in the arts–in music, painting, movies, and literature, in particular.

In movies, it can be seen in the ‘human wilds’ or natural chaos depicted by such diverse works as Deliverance, Into the Wild, Apocalypse Now, All Is Lost, Persona, Ran, Psycho, Vertigo, The Birds, Cape Fear (1962), Pierrot le Fou, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, Dog Day Afternoon, Equus, Badlands, Reflections in a Golden Eye, Mississippi Burning, The Misfits, The Mosquito Coast, Brewster McCloud, Picnic at Hanging Rock, Dances with Wolves, Dead Ringers, Crash (2005), The Godfather, A River Runs Through It, La Dolce Vita, Straw Dogs, Walkabout, Wild Strawberries, Zorba the Greek, and Lawrence of Arabia. Often there are psychological dimensions or madness to such edges. Director David Lean perhaps spoke for many of us when he enthused about his Lawrence: “I love nuts.” And so do the masses, especially loving antiheroes, psychopaths, and criminals (to wit, Silence of the Lambs and other films of that disturbing ilk).

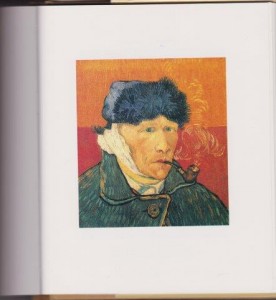

Some of the most interesting, ‘wild’ painters have included, first and foremost, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Jackson Pollock. People have found beauty and a strange aesthetic or soul satisfaction from their wild, edgy works. For examples of The Wild in music, one need go no further than Beethoven, John Cage, the ’50s avant-garde jazzmen, Jimi Hendrix, or The Who. (In Canada, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Gordon Lightfoot and Bruce Cockburn have frequently turned to The Wild, particularly of nature, for their song subject matter.) Regardless of genre, music aficionados have generally sought and welcomed the ‘wilder’, more challenging artists who have pushed the limits of music, reinventing it and us in the process.

And The Wild is to be found in the greatest works of memorable literature: The Odyssey, Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, Robinson Crusoe, Wuthering Heights, A Tale of Two Cities, Walden, The Return of the Native, War and Peace, Heart of Darkness, Ulysses, The Moon and Sixpence, Lady Chatterly’s Lover, A Passage to India, To the Lighthouse, The Waves, Mrs. Dalloway, 1984, Lord of the Flies, Suddenly Last Summer, On the Road, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the poetry of Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Robert Frost; and such diverse Canadian titles as “David”, Never Cry Wolf, Who Has Seen the Wind, Beautiful Losers, Wolf Willow, Where Nests the Water Hen, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, the poetry of Archibald Lampman and E.J. Pratt, and even those olde animal stories by Grey Owl, Charles G.D. Roberts and Ernest Thompson Seton.

The Wild, then, is potentially a very broad topic and mode of experience. For many, it superficially has more to do with Nature than people. But as shown above, The Wild runs deep and long through the history of human behavior, culture, and civilization. Like the English Romantic Rebellion of the late 1700s–early 1800s, it rears its head from time to time in history, and still drives much of what still interests or fascinates us about life today: the raw energy, the unconventional enthusiasms, the need for Nature or human nature and their many edges. Our spirits, souls, bodies, and consciousnesses perpetually and repeatedly hunger for The Wild. It goes with the territory of being human, ultimately.

…………………….

I will just add that perhaps the supreme forms of The Wild are The Wild as experienced, understood, and appreciated by individual consciousness, and The Wild as experienced by and in the Imagination.

photo credits:

-“Self-Portrait with Pipe” (Jan. 1889 by van Gogh)

-cropped close-up of much larger original photo by Roddy McDowall of Sir Laurence Olivier in the 1964 production of Othello

-lake scene east of Jasper, Alberta