Ingmar Bergman’s last film epitomizes much of what this director was all about: feelings, communication, relationships (male-female, father-son, father-daughter, mother-child), and responses to human flaws, failures, and death.

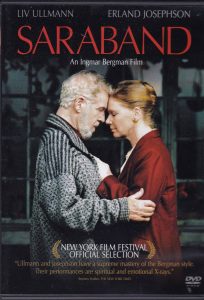

It reunites the couple from his acclaimed, intense, exhaustive analysis of male-female relationships: 1973’s Scenes from a Marriage. Johan and Marianne have entered old age and, though long separated, she has embarked on a trip to revisit Johan to experience whatever still can be experienced by the still-connected duo. Liv Ullman and Erland Josephson movingly revive their roles and take them to an ultimate, unexpected reconciliation.

But their story is truly a backdrop to another couple and family storyline Bergman initiates of Johan’s alienated adult-son and talented 19-year-old daughter, the latter about to leave home to pursue her future and bliss as a talented celloist. There are many conflicts between the two, with the musician-father controlling her cello education, but being unnaturally close to her partly because of an unresolved obsession with his dead wife. He has not truly separated from his wife and has invested his remaining life in the daughter’s forced fealty–she who will suddenly be gone for two years following a plan different from her father’s. Borje Ahstedt and Julia Dufvenius are excellent as father and daughter.

And there is the long-standing bitter feud between father and son–Johan and Henri–to complicate matters. The two share an equal support of the daughter and her aspirations, but only one of their two plans for her will win out. Marianne listens in to both father and daughter and responds to them in ways that only enhance viewers’ appreciations of the depths of her humanity, first seen in Scenes from a Marriage. She, too, has unfinished business with Johan after that and, surprisingly, with her daughter from their previous marriage–an unexpected touch reminiscent of Bergman’s Autumn Sonata between mother and adult child.

Johann’s relationship with his granddaughter is also ‘fleshed in’ with classical music playing a role in both the scenes between Karin and both her father and grandfather. Bergman also performs some magic with absolute minimal cello-playing by father and daughter, an unseen Bach organ solo played by Henrik, and a well-known classical piece on CD listened to by Johan in his interesting, atmospheric study.

And so, Bergman surprises the viewers, returning from Scenes of a Marriage, with these many unanticipated layers of themes, conflicts, and characters, saving one of the latter for a surprise ending. Mention should also be made of Bergman’s use of framing with Marianne surrounded by photographs on a table at the beginning and end of the film, and her theatrically setting-up the return visit before viewers become quickly absorbed in the movie per se of Saraband.

Saraband is thoroughly entertaining, rich, and intense like the best of Bergman’s classics. It is also his last words on human relationships, death (the pitiable, tragic Henrik presents Bergman’s view of it in the middle of the film), and film-making. Only a genius could have crafted Saraband so lovably, powerfully, and memorably. As highly recommended as any of Bergman’s classic works.