Part 1:

‘Twas quite focused on the Beatles’ relationships. John comments, in passing, that Ringo had previously been unhappy (when he offered to leave the group which surprised the other 3).

On the other hand, Paul’s influence and quality songs, through Revolver, Sgt. Pepper’s, and Magical Mystery, were definitely keeping things afloat after Epstein’s death. The songs are mostly his with the odd “I Am the Walrus” by John and better George songs now being available for use.

He even admits that he feels like he’s been taking charge and you can see it in the original Let It Be film and this one. It is very hard to imagine those 4 albums plus Let It Be and Abbey Road without Paul’s many memorable songs.

By this point, Ringo and George recognize they’re second bananas to Lennon-McCartney.

Ringo looks bored and remains patient, accepting all. George has new songs which Paul and John are not giving a fair listen to. And Paul keeps suggesting to him what he might play.

Eric Clapton, a better guitarist than George becomes an instant possible replacement (and George knows his friend is a better player–later he would use him on Cream’s “Badge” and Clapton would marry Patty/”Layla”, G’s first wife). He feels the olde democratic group feeling is disappearing or gone. He does not accept the changing dynamic, questioning it all the way.

So the dam, predictably, bursts, George quietly and firmly exits, and at the end of part 1, we learn that there was no resolution after the other 3 visited him at home.

That all said, the whole process of completing this project within a certain time frame (they always had worked that way before with every previous project–Epstein and Martin kept them hopping), working in a cold winter barn of a building with inferior equipment and Martin no longer in charge of the recordings, quickly wears on them as they flop around trying to dig up and create material for the show. (Martin did not produce this album BTW–Phil Spector took over with John’s approval and nobody else’s–more conflict plus the lawyers’ conflicts)

Lots of dead ends, and growing unhappiness, anger, and frustration. There is a certain truth to the original feel and surfaces of the Let It Be film.

Slowly, though, the album’s songs start emerging in raw forms, but the standouts come more prominently from Paul, starting with “Get Back” (which nearly became a politics-of-the-day song!), “Let It Be” (which he noodles away on in the background as others talk oblivious a masterpiece is emerging), “The Long and Winding Road” (being worked out as Paul talks to the equipment mgr./go-fer Mal), and “Two of Us” (the best of the old LM songs)–the 4 bona-fide classics from the album.

It is fascinating to see Paul work through his songs, literally ad libbing and giving birth to them on camera. And it is fun to see the guys (especially L and M) really enjoying themselves and each other as a close-up duo.

Right there is the core of their connection, success, and evolution as songwriters and performers. Right there is the core of The Beatles, though George and Ringo always made major contributions, performances, and enhancements.

But about a few things, Paul was very right: you need a vision, you need to keep pluggin’ away till you get the results you want, and the best tunes will eventually emerge. And they do, eventually, for the Let It Be film and album.

Very interesting overall, I got my money’s worth on creative process and behind-the-scenes Beatles live. What I didn’t bargain on was the painstaking detail about a group breaking up, Paul and George’s conflicts (Paul even questions the grammar of one of George’s lines! Woh!), and how little distraction Yoko actually created on set (it was like she wasn’t there as far as the other 3 guys were concerned).

Lots of sitting around waiting for George to return, for their Apple recording studio to take shape after they abandon the Twickenham barn, for their machinery to arrive, for John and Paul to stop goofing around between recording takes, and for their recording engineer to be ready to record. The secret recording of John and Paul’s private conversation about getting George to return is bizarre with nothing resembling common sense or productive thoughtful statements!

There are more scenes giving insights into their creative process with George Martin stuffing newspapers into a piano to make it sound more quaint and dated, with John on Hawaiian guitar on George’s “For You Blue” skiffle tune, with John on guitar playing the bass parts for “Let It Be”, and with John and Paul in rehearsal trying different accents including Dylan and Scottish on “Two of Us” run-throughs. The part where John and Paul go through the harmony syllable by syllable on the ending of the bridge is a minor study in painstaking detail.

Many songs that made it to the Abbey Road LP instead are heard here in process including “Oh, Darling”, “Mean Mr. Mustard”, and “Golden Slumbers”. A number of other song starts end up on Paul’s solo albums: including “Teddy Boy” and “Back Seat of My Car”.

Excerpts from many old rock songs including their own material continue to pop up, reflecting their early and other musical influences, the highlight of which is when John and Paul sing a chunk of The Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love”.

As previously in this film, George and Ringo remain more obviously on the outside of conversations and decisions. Paul often looks to John for direction and tends to follow him for goofy outtakes; John is usually the mischief-maker keeping things light, breaking up Paul although Paul likes to ham it up whenever it’s his song.

People continue to drop in for a look-see including Peter Sellers who had worked with Ringo on The Magic Christian movie, Yoko’s art dealer, and notably pianist Billy Preston whom they immediately get on board for some rehearsals and eventual concert. A fair bit of work gradually begins to be put in on album songs such as “I’ve Got a Feeling”, “Don’t Let Me Down”, “For You Blue”, “Get Back”, and “Let It Be”.

George Martin keeps offering opinions, but has been largely sidelined throughout the film so far. In fact, EMI later gave the tapes to Phil Spector to finish up, going against John’s original intention of a bare-bones live album (those original tapes were not heard till the Naked Let It Be CD years later). Phil Spector got most of the credit for the Let It Be LP; George Martin only got a minimal, humiliating “Thanks” on the cover.

Thus, it’s understandable when at one point when Peter Jackson shows the bored and disillusioned Martin curled up on the studio floor in a vaguely ‘fetal’ position trying to pass the time reading a newspaper. (Elsewhere Martin has spoken of songs with 53 takes which frustrated him to no end when he gave advice at the time; he was often ignored though he was asked later to produce and record the group for Abbey Road ‘the old way’ afterward.)

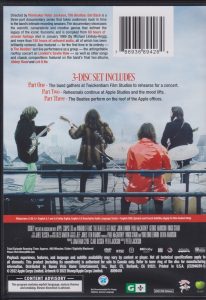

Near the end of part 2, the original director and recording engineer confer with Paul, suggesting an Apple rooftop concert and Ringo and others go up on the roof to check things out. (There is some concern that the roof might not hold all the equipment and people on it.) So they have found a stage and only have to finish rehearsing days away from the planned show.

Part 3

The original Let It Be project was a slow, often tedious month-long project in the depths of London winter–January, 1969. Up to this point, about 3 weeks in, traction has been snail-like with numerous obstacles (the inhospitable Twickenham ‘barn’ locale, setbacks (George leaving the group in Part 1), and waiting around (the Apple studio was not fully ready for recording and the group still had not settled on a performing venue until days beforehand).

As things are picked up in Part 3, with 3 days to go for the ‘show’, they are still waiting around as Ringo and George work on the former’s “Octopus’s Garden” which, like several of the rehearsed songs (“Oh Darling”, too), ended up on the superiorly recorded album Abbey Road, under the more conservatively, reined-in, moderating auspices of their producer George Martin, in this project much marginalized and later controversially overproduced by American Phil Spector.

Linda, Paul’s new love interest, and her daughter drop in and the young girl mixes freely with the goings-on, bringing out more playful aspects of everyone in the studio. ” A wide range of non-album songs continue to be sampled including “Kansas City”, “Blue Suede Shoes, even Beatles’ oldies like “Strawberry Fields Forever”.

George confesses he has spent 6 months already developing “Something” and the band, more conscious of receding time, rehearses “I’ve Got a Feeling ” without Paul. An early hand-held synthesizer is briefly tried out, one that came back later, refined, on Paul’s successful Band on the Run LP. There is also an early version of Abbey Road‘s “I Want You” (they, incidentally, enjoy and get into playing wilder numbers throughout this movie) as they continue to fool around (e.g., John and Paul’s clenched, closed teeth version of “Two of Us”).

They talk about improving the studio sound with Martin and also their tuning, which has been rough throughout the film so far. (BTW some of that slightly skewered effect has to do with Preston’s electric keyboard, that never fully meshes seamlessly with the concert guitaring also.)

Things are moving forward in recording, but the viewer starts to realize that the amount of fooling around and goofing off when they rehearse was part of the Beatles’ usual modus operandi. They were easily distracted, getting other famous songs ‘out of their systems’ before settling down to record. (A fact I can confirm from another evidence source, the Unsurpassed Masters CD bootleg series with its numerous stops and starts and other distractions.) In other words, Beatles rehearsing often went this way and was this labored and distracted during their recordings. *The only time we hear the band go all the way through songs is on the finished LPs and in live performances. If the viewer is a musician, there’s definitely a familiarity with the effects of cold weather on the hands of players and instruments confirmed by John trying to keep his hands warm outside on the roof. Ironically, the concert sound remains relatively tuned and clear. The set is very limited; we hear none of the piano songs and any of George’s material for the album, unfortunately. (Important to note, too, is that the group had no monitors so could not hear each other as they played. And that the recording set-up didn’t know what the actual concert would sound like until they started playing.) Visually speaking, Lindsay-Hogg’s split-screen effects during the short show keep things interesting until it’s over.

Finally, we do hear complete versions of some of the album’s songs including “Get Back” (twice), “Don’t Let Me Down” (twice), “I’ve Got a Feeling (2x as well), “The One after 909”, and “I Dig a Pony”. To their credit, the band pushes the envelope with deliberately mangled words, screaming, and in-between-numbers comments by John. No one watching on site seems to mind the less-than-perfect run-throughs given the remarks of most spectators. Later the band retreats to the bowels of the recording room to listen to the satisfactory playback results in a brief celebration party atmosphere.

Jackson’s ‘macrocosm’ Get Back film has been very comprehensive on the making of Let It Be over a long dreary calendar month; he seems to leave nothing out and the steady flow of jump cuts to more interesting or fun moments keep the viewer watching and along for the ride. It, of course, could have been a shorter film–maybe 3 hrs. in 2 nights? And I believe the final effects from that choice would have produced a better film overall. Instead, in his service to footage-hungry fans, Jackson serves up too many editable tidbits that peter out or lead nowhere to quick dead-ends.

Let It Be, Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s original dreary film was definitely more edited and focused and, therefore, was suited for a movie crowd with the concert footage at the fore in its ending. Jackson’s film projects the same long dreariness and waiting around for things to happen. But he also highlights many brighter moments reflected in the lighting, the constant joking around and sidetracks, and the Beatles’ more developed character portrayals. For that, he deserves a lot of credit and has ultimately rendered a truer, more realistic picture of what happened in that month-long ordeal and process.

And it is that more positive approach/response Jackson leaves the viewers with in the end credits with amusing outtakes of songs from the film. Perhaps in the greater scheme of things, it is the humor and fun of making Let It Be that matters and mattered most and the fact that so many others got to enjoy it including The Beatles’ last live performance. His film is a respectful retrospective ode to the group and their love of music and performance. Long will they be remembered and immortalized that way.