in 1967 and still does today:

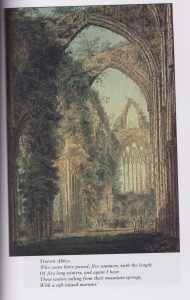

After reading the first stanza, I recognized that, first and foremost, Wordsworth was writing about the “beauteous forms” of Nature (the first time I’d ever heard that wonderful adjective).

And then, I thought back, too, to how much pleasure Nature had given me even when later recollected.

At age 17, I thought to myself that “acts of kindness and love” were about as good as it got in terms of the actions of humankind.

As a rebellious adolescent, I agreed with the phrase “this unintelligible world” which tied in with our studies of Hamlet and his various conflicts and dilemmas.

The line “We see into the life of things” was that special Hamletian facility which I also sought at the time. The poet had convinced me by this point in his poem that Nature was a logical, perfectly plausible way to “see into the life of things”; Nature, indeed, taught many lessons and gave valuable insights.

“Glad animal movements” was the most perfect expression I had ever heard then of my “boyish days”. There was that kinship with Nature from the get-go for this only child. The confusion of youth is embodied in the next line; “I cannot paint/What then I was.” Also expressed in the boiled-down “The sounding cataract/Haunted me like a passion”. Again, one could only say at that time, approximately, how one felt, but that image captures both beauty and chaos of the sensation experienced: a “beauteous form”.

“The still, sad music of humanity” pretty much summed up to me my-then emerging overall sense of humanity and human history–including its pain and suffering.

“Elevated thoughts” were starting to happen for me beyond that Beatles time: the more thoughtful ideas and epiphanies via Simon and Garfunkle and Bob Dylan in music, for instance. Increasingly, I was being exposed to via music, literature, and poetry more of “a sense sublime”.

Much as in Hamlet’s case, thoughts began moving, tumbling. There was an accompanying “motion and a spirit” that seemed to roll “through all things”.

Context-wise, these “objects of thought” were inspired by and echoed by Nature as Wordsworth points out.

One main message of the poem was: “Knowing that Nature never did betray/The heart that loved her”. Through the years, subsequently, there remains something true and fundamental that remains and evolves from a love of Nature. It has its own rewards, so to speak.

Above all, I recall then thinking ‘This is me! This is what I have been and still am. Nature was something I loved and appreciated in my childhood and youth.’ I was and would always remain “So long,/A worshipper of Nature”.

…………………………..

Etc.

At the same time, we studied “Composed upon Westminster Bridge”, a fine Wordsworth sonnet which echoes what he says in “Tintern Abbey” about the peace and insights through Nature in its many “beauteous forms”.

Much later, I would encounter and teach, in my adult years, his “Ode: Intimations of Immortality” which greatly echoes and extends the thoughts of “Tintern Abbey”.