(Famous Swedish filmmaker Alf Sjoberg’s adaptation-homage of Strindberg’s famous 1888 play later, incidentally, led the way to his collaboration with a young Ingmar Bergman on another movie and influenced Bergman’s early filmmaking thematically and stylistically.)

This notorious single-act play used many stylistic devices including tracking shots of horses and carriages, dream scenes, multiple flashbacks to childhoods of two characters, dissolves, plays on light and shadows, and visual symbolism such as a birdcage, the ‘Garden of Eden’ estate, the park nude statues, and large European paintings in the house. Sjoberg’s goal was to open up the play which basically took place in one room on stage, in order to make Miss Julie more entertaining, interesting, and understandable to filmgoers of his day.

He also used some controversial content like nude boy and the same clothed boy escaping an outdoor biffy by crawling through one of the toilets, and later getting whipped (offscreen) by his father to appease his employer’s manservant who chases after him. Sex, too, is thickly suggested and referenced in this movie and the film was banned in the U.S. when it first came out.

This tragedy is centered on Miss Julie, an aristocrat’s daughter raised by weird, manipulative parents, who was raised by her mother to treat men like dirt. She becomes heavily involved with her manservant Jean who uses her for his ends, eventually leading to tragedy for both of them. She humiliates him early on, flirting shamelessly with him despite their class differences. Later, Jean degrades her and uses her to steal her father’s money so they can escape to France to open an inn.

There is a definite modern S & M undertone to this struggle between the sexes as a ‘liberated’/new woman is disgraced and exploited in a manner representing 19th century’s male treatment of women. Julie meanly whips her dog Diana, but she is also seen using her whip on men. There is one scene where Julie’s father shows off a painting of his mistress/bride-to-be to a roomful of envious men (unabashed male gazing of the woman as object).

In flashbacks, the story of Julie’s parents, their manipulative relationship, and the control games they play over Julie become almost as important as the main Julie-Jean plot, and act as psychological background as to why Julie is the defective way she is. Her mother is a manhating misandrist who warps Julie’s sense of the male sex. Her disgraced, chauvinistic father treats her better and looks out for her more. The crazy mother sleeps with the father’s friend and sets fire to the house; her husband eventually tries to commit suicide.

Certainly, ‘forbidden fruit’ Julie is mentally unstable, to say the least. She is also terribly selfish, uncentered, fickle, provocative, mean, and suicidal. Both she and Jean trade childhood memories and even strange dreams that exemplify their core views of life. In many ways, they are alike: restless, callous, rough, and soulless. The caddish Jean is terribly shallow, hedonistic, and materialistic; despite their class differences, he has no qualms about making her a stereotypical fallen woman. Julie herself becomes the bird cage symbol used in the opening credits. Though she is manipulative in the first part of the film, she becomes an exploited, used creature by the end.

I will add that many of the characters’ psychological depths are communicated non-verbally beyond words, and via an emotionally-cueing melodramatic soundtrack. Simply put, this aesthetic black and white film covers a lot of territory in 90 minutes. And Sjoberg does finally succeed in making Strindberg’s play more accessible to modern audiences via the medium of film. The movie is truly an irrational inter-generational battle of the sexes by Strindberg with Sjoberg’s social criticism baked into it all the way.

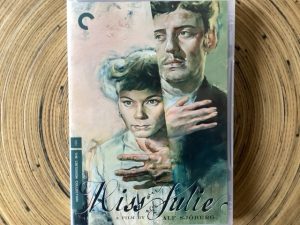

(DVD includes interesting essays and many extras. Restored and subtitled in English)