Pretty obvious why Hallmark would have developed Hardy’s 1978 novel, which I studied and quite enjoyed in grade 12, 1967. The book has 4 main women characters including Eustacia–the obsessed, dreamy, wild young woman of Egdon Heath whom residents suspect is a witch and who is destined for tragedy, Thomasin–the naive, innocent, ‘average’ woman of the day who stands by her man and gets a happy ending, Mrs. Yeobright–the mother who is ignored by her niece and betrayed by her son and daughter-in-law and suffers a pathetic end, and Susan Nonsuch–the superstitious peasant woman who has it in for Eustacia.

Thus, the bent of the movie features the women characters prominently which, in turn, diminishes the interest in the three main male characters: Clym–the idealistic “native” scholar returning home who–despite two tragedies–follows his bliss to become an itinerant preacher trying to educate the ignorant Egdon peasantry, Damon Wildeve–a handsome, wild philanderer who strings out three women, and Diggory Venn–the intervening reddleman who hangs around the heath, watching out for Thomasin, and who shows up in several scenes mitigating key moments.

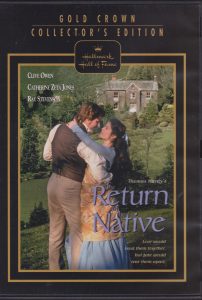

That all said, the heath is decently represented in the opening scenes; the heath is like a character in the book and figures in all the main scenes and events. Zeta Jones looks and acts like Eustacia–the book’s focal character. Clive Owen makes a nice edgy Wildeve, Ray Stevenson as Clym, is a typical Hallmark-looking male lead, Steven Mackintosh makes a convincing, concerned reddleman, and Joan Plowright is perfect as the wronged, suffering mother. The movie focuses almost exclusively on the male-female relationships without many nuances from Hardy’s book. It is faithful to the original plot and the book’s fans won’t feel that any of the main storylines are given short shrift other than the interesting, developing relationship between Thomasin and the reddleman at the end, which Hardy introduces to prepare for their getting together.

There is lots in Hardy’s novel to interest any film producers and many audiences. But, as said above, the movie’s mood and tone (reflected in the music) lean heavily on Hardy’s book’s romantic side. What gets significantly lost are the great comic scenes, the depths of misunderstandings, and much of the tragic foreboding and suspense. Hardy was a much better storyteller–narratively, descriptively, and dialoguely–than this movie suggests. In short, read the book first. It’s a bona fide classic on the relationships between men and women, the themes of fate, bad luck and bad timing that Hardy was obsessed with, and the sheer beauty of the writing and its values as literature. Suffice to say, reading the novel creates a much fuller, richer, more intense experience and movie in the imagination than the Hallmark adaptation.

No question the place to start with this title is the original novel. Six sample pages below:

After this novel, came the ‘Shakespearean tragedy’ The Mayor of Casterbridge, the unforgettable Tess of the d’Urbervilles, and his last, harsher, and critically-panned novel Jude the Obsure–the latter which caused Hardy to abandon novels altogether and begin writing and publishing poetry at the end of his writing career. But Far from the Madding Crowd (his first success) and The Return of the Native have a nice accessibility about them with readers that have long kept them popular books in his indisputable, interesting canon.