Anthony Burgess’s prophetic novella A Clockwork Orange was first published in 1962 in the U.K. It received a world-wide release in 1972, about the same time as Stanley Kubrick’ highly controversial and banned-in-the-UK 1971 movie.

The novella is narrated by a futuristic 15 year-old street thug Alex in Nadsat–an imaginative Russian-inspired argot. For curious readers wanting to engage further with the book, I include this link of Nadsat vocabulary and expressions. Appendix:A Clockwork Orange – Wiktionary

Alex and his droogs (mates) wreak havoc on Londoners until he is arrested and ‘rehabilitated’ by the equally sadistic Ludovico’s Technique, which conditions/destroys Alex’s inner workings, leaving him a ‘Clockwork Orange’, susceptible to violence by others.

Burgess imagined and created a unique, horrific future which prompts reader thinking and discussion about sex and violence, crime rehabilitation, free will and social control, and socially-sanctioned conditioning. This is a book about which to is impossible not to have reader/viewer moral reaction, position, or stance. (Even Burgess later had regrets about the effects of his book and Kubrick’s movie.)

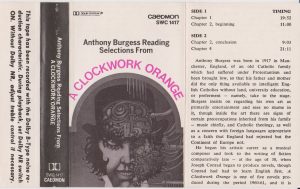

For anyone wondering what the book might sound like when it is read aloud, the author narrated it on one of the last (rare) Caedmon audio-cassettes.

From an email of mine about the book:

Kubrick’s deliberately provocative film was an over-the-top adaptation/extension of Burgess’s book. Sort of like what he did with King’s Shining, similarly pissing off the author.

Extremely controversial, it was pulled in the U.K. after police came round to Kubrick’s remote rural home to warn him of a possible break-in by thugs inspired by the movie.

Elsewhere, it played the world, sometimes in chopped form.

Burgess was also pissed at him for releasing a pictorial book version exploiting the author’s original.

So book and movie are two separate, superficially-related entities.

The book.

I find it hard to believe it was originally released in the U.K. in 1962!

Burgess had just gotten back from a Leningrad trip and used Russian language throughout Alex’s rants.

BTW/he resisted allowing a Nadsat vocab list to be attached to the book.

He was smoking 80 cigarettes a day and drinking copiously at the time he wrote the book.

He was also being checked out for cerebral damage about the same time!

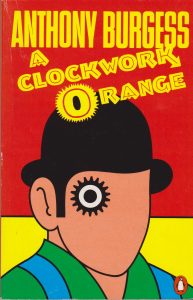

The North American book version was released in 1972 with the eye-catching cover art and became a best seller just as Kubrick’s movie was landing in N. Am.

It omitted the last chapter from the originally in which Alex has settled down, is no longer hyped up, and desires to have a conventional life with wife and child.

About this, Burgess had mixed feelings, but could see the point of the now-vulnerable, beat-up Alex ending.

In years afterward, he continued to reveal mixed feelings about the book.

Which is perhaps partly reflected in his energetic Caedmon cassette/LP reading (as/after you hear it, Alex’s expressions are less obscure and what is going on becomes much clearer) which climaxes with the teeny bopper romp and Alex zonked out on Beethoven and drugs!

On the tape: no reclamation, no Ludovico’s Technique, no retributions by those Alex had wronged. No 2nd part!

What Burgess had seen (today’s relevance) of how the Soviet Union treated individuals inspired the last part of his book along with Skinnerian manipulations.

There is also something of the 1944 rape of his first wife during the blackouts by US soldiers while Burgess was off to fight in the first part as well.

So he was imaginatively writing from/out of his life.

Burgess was unquestionably, though, pro-freedom of individuals vs. the tyranny and torture by the state. Essentially, the book was serious-minded satire about an imagined dystopia.

What I immediately glommed onto when I first read the book was Alex’s voice and the colorful, powerful Nadsat language.

For me, the tour-de-force language trip drove the vigorously-written book and successfully created a brutal dystopian world every bit as powerful as Orwell’s, Huxley’s, and Bradbury’s.

Is there a lot of uncomfortable truths about individuals, hooligans, societal controls, the destructive use of technology and psychology?

Yes, and that’s what makes its truths very powerful much like the self-flagellation in Brave, and Room 101 in 1984.

And the movie? It remains a whole other sensational beast unto itself, a reflection of Kubrick’s visual and aural choices, and his most provocative film.