Relatively speaking, Netflix is a very mediocre, mundane, unremarkable source of movies; it lacks many of the great titles of all time including works by great directors and writers, starring great legendary actors. Today, serious and truly great movies have truly fallen on very hard times. One, in many cases, has to go back to before 2000 to find quality and great films.

If you are a truly serious film aficionado, I suggest you first get hold of one of the yearly movie guides of Leonard Maltin and Roger Ebert and seek out 4 star films of the past. And, if you want to know who and what to collect, I can’t think of a better director to start with than the legendary Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980) who directed 61 movies, 30 of them being post-1926 bona fide classics, and something like 10 masterpieces . (He also directed 20 episodes of his popular tv show Alfred Hitchcock Presents with their funny self-mocking introductions by the Master himself).

Hitchcock started in the silent movie era in England before transitioning to Hollywood in 1940. He mostly made thrillers, highly entertaining, largely successful commercial films. He was nominated for Best Director at the Oscars five times, but never won. He won several prestigious awards including the American Film Institute Award and the Directors’ Guild of Lifetime Achievement, and had 2 stars on Hollywood Blvd. as well as being knighted by the Queen.

Hitchcock pleased his fans by making short speechless guest appearances in each of his films. He was very close to his wife, script writer Alma Reville Hitchcock, who had a hand in many scripts. His daughter, Patricia Hitchcock appeared in a few of the films and she has done an excellent job in keeping his film legacy intact with many special releases.

Although Hitchcock compared actors to cattle, he used many famous stars including Laurence Olivier, Joan Fontaine, Cary Grant, Joseph Cotten, Ingrid Bergman, James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, Eva Marie Saint, Janet Leigh, Tippi Hedren, Sean Connery, Farley Granger, Robert Cummings, Claude Rains, Gregory Peck, Montgomery Clift, Henry Fonda, Ray Milland, Shirley MacLaine, John Forsythe, Doris Day, Paul Newman, Julie Andrews, Anthony Perkins,Peter Lorre, Teresa Wright, Jane Wyman, Robert Walker, James Mason, Jessica Tandy, Bruce Dern, and Karen Black.

He used scripts by such notable writers as Sean O’Casey, John Buchan, Thornton Wilder, Joseph Conrad, James Hilton, Robert Bloch, Dorothy Parker, John Steinbeck, Brian Moore, Patricia Highsmith, Frederick Knott, Evan Hunter, Ernest Lehman, Daphne du Maurier, Leon Uris, and Joseph Stefano, and used such collaborators as cinematographer Robert Burks, Surrealist artist Salvador Dali, titles specialist Saul Bass, and composer Bernard Herrmann–cf the tribute to the latter at the end of this piece. When assessing Hitchcock’s achievement, one must remember mentioned in the last paragraphs who all made special contributions to the quality and greatness of his achievements.

Hitchcock mentally visualized his films before shot them and always said that those versions are better than the finished products regardless of how many of these became classics. He had several motifs which he re-used including the wrong man, the extended spy adventure-chase, dual characters/alter egos, psychological problems, murderers and psychopaths, guilt and suspicion, traps and prisons, failed romances, worlds gone crazy, good and evil, and macabre humor.

Select Hitchcock Classics

1927: The Hitchcock story really begins here with this silent movie inspired by Jack the Ripper.

1935: a classic pre-North by Northwest espionage-adventure chase.

1938: another good one; last of his British classics.

1940: his first Hollywood film, based on a Daphne du Maurier novel, which won Best Picture at the Oscars. Disc (Joan Fonatine and Laurence Olivier) is from the well-done Premiere Collection (below) which showcases early Hitchcock movies.

1940: a good propaganda movie he did for the U.S. starring Joel McCrea.

1941: suspicion and guilt explored intensively; Johnny, a fascinating sociopath played expertly by Cary Grant; Fontaine won Best Actress Oscar. Weak ‘happy’ ending was not Hitchcock’s choice.

1943: one of Hitch’s favorites–a masterpiece about innocent good and cynical murderous evil using dual Charlies (Cotten makes an excellent psychopath); Thornton Wilder worked on the script.

1946: Grant again, this time as a callous manipulative spy, with Ingrid Bergman playing a victim used by Nazis pursuing the first famous MacGuffin.

1951: underrated exploration of good and evil with excellent psychopath played brilliantly by Robert Walker; many quirky touches with Hitchcockian black humor.

1954: closely adapted from a famous play, shot on 1 set; famous for 3D alternate version and gruesome scissors murder; Ray Milland plays a charming, sympathetic villain and Grace Kelly, the first platinum blonde Hitch would be obsessed with.

1958: a core H classic–the ultimate romantic fallacy film; heavily unconventional study of obsession with vertigo and hallucination touches thanks to special effects camera work; Stewart plays the most deluded man in cinematic history.

Typical of the kinds of book analyses of Hitch’s best films; dust jacket echoes title designer Saul Bass’s work at the beginning of the movie.

This illustrated book features actual places used by Hitch in the filming of Vertigo and other films of that time.

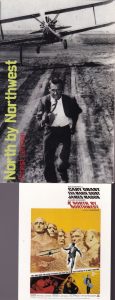

1959: a masterpiece espionage comedy-thriller; lots of fun wisecracks and a chase across America which ends at Mt. Rushmore; Grant has never been better; the cornfield scene is worth the price of admission.

left, top: the actual script by Lehman; right: locale that inspired the climax

1960: from one masterpiece to another; it does not get more suspenseful than the deliberate black-and-white/Gothic-filmed Psycho; Anthony Perkins makes a perfect Hitchcock psychopath; shower scene is a powerful memorable classic scene, punctuated by Bernard Herrmann’s music which helped propel the director to world-wide fame and notoriety.

the source novel for the movie

Personal association copy signed by the author.

It was inevitable that Janet Leigh would revisit the shower scene and her experiences working with Hitchcock.

1963: speaking of platinum blondes, ‘Tippi’ Hedren, whom Hitchcock named; based on an end-of-the-world short story by Daphne du Maurier, this film used tame and fake birds for the vicious attacks, traumatizing Hedren in the shooting; this is his ultimate special effects movie with electronic soundscape by Bernard Herrmann; many powerful memorable scenes in this classic.

Even Camille Paglia got around to analyzing it!

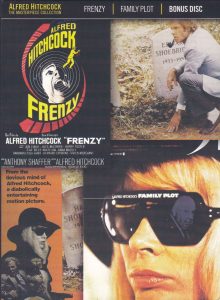

1972: one of my favorites; Hitch went back to London to shoot this one based on his ‘wrong man’ motif; Jon Finch effectively plays an unlikable protagonist (everyone is unlikable in this one) who is, nonetheless, innocent of the Ripper-style strangulation murders going on in hip seventies London; spoiler: Barry Foster plays the malevolent Hitch psychopath of all in a sexier than usual Hitchcock.

The original novel.

The colored discs shown above are all from the very interesting lineup of this box set. Several must-haves here including Rebecca, Notorious, Spellbound, Lifeboat, and The Lodger.

Two thumbs up for bringing back some films previously out-of-print or unavailable; many extras, especially the Spellbound ones.

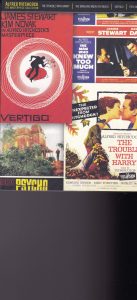

This is simply a must-have boxset with many of the core mature classics; many extras as shown below. I particularly appreciated the movies of Rear Window (1954)–featuring a courtyard set, Saboteur (1942), The Trouble with Harry (1955), Rope (1948)–based on Loeb-Leopold murders and shot in 10 min. continuous segments, The Man Who Knew Too Much (featuring “Whatever Will Be, Will Be” Oscar song winner), and Torn Curtain--all compelling and entertaining with Rear, Rope, Trouble, and Man being genuine classics.

The AFI Salute to Alfred Hitchcock shows Hitch being lauded with film excerpts in a large Hollywood dinner setting featuring many stars.

There are many books about the director. This is a good place to start with treatments on each of the main films.

This is a more recent, interesting overview of the films.

Spoto gives concise brief analyses of each film–the characters, conflicts, themes, motifs, and techniques.

This was a classic series of interviews between Hitchcock and his big-fan French director Francois Truffaut.

Many years later, recently, this DVD was released with some interesting extras.

An oldie, VHS, hosted by actor Cliff Robertson reviewing Hitch’s career focusing on his dark side and pessimistic messages. Recommended.

This comprehensive labor of love features colorful posters and lobby cards for each of the films.

………………………………………………………….

Sidebar: The World of Bernard Herrmann

One of the most prolific, yet under-appreciated soundtrack composers of all-time. ‘Benny’ worked with Hitchcock for 9 pictures (The Trouble with Harry, The Man Who Knew Too Much–also conducted at Royal Albert Hall in the climax, The Wrong Man, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, The Birds–electronic music, Marnie, Torn Curtain–unused score), Orson Welles for 2 pictures (Citizen Kane—his first film, 1941, The Magnificent Ambersons), Brian De Palma for 2 pictures (Sisters and Obsession), Francois Truffaut for 2 pictures (Fahrenheit 451 and The Bride Wore Black), as well as Martin Scorcese (Taxi Driver–jazz score, his last film, 1976), Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and Robert Wise (electronic music for The Day the World Stood Still).

He also did memorable, distinct, striking music for *The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941), Jane Eyre (1943), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947), The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952), *Garden of Evil (1954), *Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1959), Tender Is the Night (1962), and *Cape Fear (1962).

The bio.

A fascinating VHS/DVD with many scenes shown with Herrmann’s music.

It all began with working on Orson Welles’ 1941 classic, one of the greatest films of all-time, which wouldn’t have been the same without Herrmann’s carefully chosen pieces.

His first film (1955) with Hitch features a lighter, humorous, playful soundtrack.

1957: One of Herrmann’s best along with the next three. It is simply impossible to imagine these three movies without the brilliant music of Herrmann.

1959: Quite a variety of music and styles with the great opening fandango music.

1960: String music has never been the same since Psycho. The shower scene is weak and much less scary without Herrmann’s music. A masterpiece of film scoring.

1964: Again it’s very difficult to disentangle Herrmann’s contributions from Hitch’s most memorable movies.

The last unused score for Hitch which the director was pressured to change by the studio for a more modern pop-y sound. Fortunately, we have this CD which proves Hitch was out to lunch by using no music in the gruesome gas-oven murder scene; Herrmann’s music would have made this scene 10 times more dramatic, moving, and effective. The two parted company after this incident.

Herrmann landed with Truffaut next the same year, 1966. This soundtrack made Fahrenheit more futuristic, dreamy, and ultimately deeply romantic.

Originally scored in 1962, you can hear this spooky, eerie soundtrack thanks to a remake of the movie by Scorcese with Elmer Bernstein conducting.