Larger-than-life director-actor Orson Welles (1915-1985) started at the top and worked his way downward, as he put it, beginning with Citizen Kane (1941), what has long been considered the #1 Best Film of all-time by many critics from the 1940s to the 1990s.

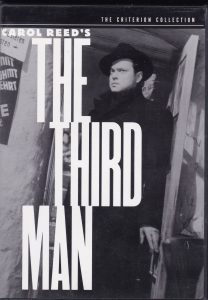

He was a memorable presence in unconventional, maverick film-making and is one of the first film directors to give rise to the term “auteur” relative to complete control over his black-and-white movies including hustling, financing, producing, promoting, writing, adapting, acting (including dubbed-in voices), cinematography, editing, art direction, set design, even costume-making. A genius, he had a thorough hand in everything he directed and even directed himself acting in other people’s pictures (“The Third Man”). And he truly enjoyed good movies, proclaiming film-making to be “this happy lunacy”.

In one oft-repeated quip, he once introduced himself to a small audience in a town beset by a bad snowstorm: “Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. My name is Orson Welles. I am an actor. I am a producer. I am a director. I am a magician. I appear onstage and on the radio. Why are there so many of me and so few of you?”

Always busy even in his exile years from Hollywood, he left many projects uncompleted including films of It’s All True (1941-42)–a documentary which RKO halted, Moby Dick, Don Quixote, and King Lear. He narrated many films and did tv commercials when he was broke including the famous Paul Masson wine ones. Famous documentaries have been made about him (The Eyes of Orson Welles), his work (about The Panic Broadcast, his battle with William Randolph Hearst–the model for Charles Kane), and The Cradle Will Rock 1937 Broadway play.

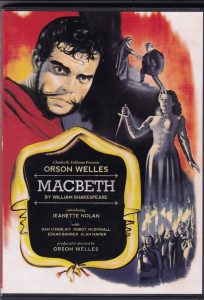

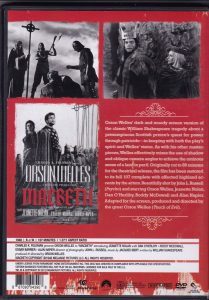

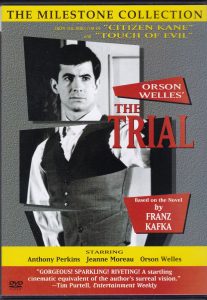

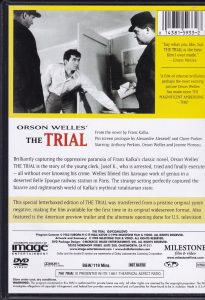

Welles made the first significant movie about the failure of the modern American Dream–Citizen Kane, homages to the past (the new and old Americas in The Magnificent Ambersons), studies of corruption (1949’s The Third Man with Welles as the charismatic gangster Harry Lime), 1958’s thoroughly sordid Touch of Evil), tales of love (1951’s Othello–shot brokenly over 3 years with changing European locales as Welles struggled for financial backing; 1968’s The Immortal Story), unusual documentaries ( 1973’s F for Fake), Shakespeare adaptations (1948’s Macbeth–shot in 23 days using Scottish accents, 1965’s tour de force Chimes at Midnight which combines the Henry V plays, but focuses on Falstaff), heroic and anti-heroic leading man characterizations (1943’s Jane Eyre as Rochester; the rogue in 1947’s The Lady from Shanghai with its famous hall of mirrors conclusion), and novel adaptations (1962’s The Trial based on Kafka’s book, shot in the humongous, deserted Gare d’Orsay train station).

Welles was not only a cinematic force to be reckoned with, a Boy Wonder, an enfant terrible, a maverick, but an ideal in the world of film direction as well as a cautionary tale about the dangers of ceding too much power to independent film-makers. A part-time performing magician he always managed to pull rabbits from his project hats: the last and latest one being the completion of, by Peter Bogdanovich and other friends of his the unfinished film, The Other Side of the Wind (2018) now available only on Netflix–his riskiest, artistic statement of his career, which he previewed as early as AFI’s 1975 salute to him.

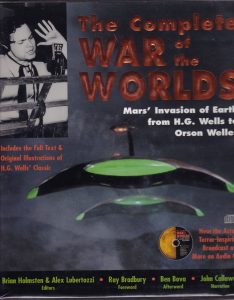

1938: Welles created a sensation when he sent millions of radio listeners into the streets during and after this Mercury Production of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. This nice, over-sized book also contains a CD of the original broadcast.

Contains the script and much else about the broadcast.

In 1953, a color film starring Gene Barry (tv’s Bat Masterton) came out.

A 2005 2-DVD documentary extending the controversy’s discussion. About the same time, Welles did an all-black Macbeth at a Harlem theatre which created another sensation. Soon Hollywood came calling and gave him the controls of what he called the best electric train set available.

1941: His first film was an instant classic though poorly attended because of Hearst’s newspapers’ and theatres’ boycotts. Welles and RKO had to rent a theatre in New York to have his movie shown there. He only won a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. This 2 DVD set contains The Battle over Citizen Kane documentary. There were numerous innovations including low angle cinematography showing ceilings and a dubbed-in opera singer singing off-key deliberately.

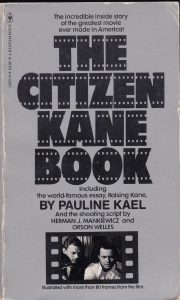

Left: Critic Pauline Kael features the script and background on the fight between Herman Mankiewicz and Welles over script rights. Right: there have been many critical books written about Kane.

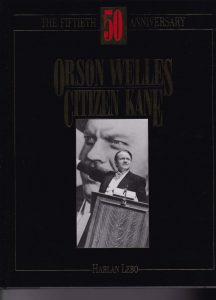

Left: In 1991. Turner Entertainment issued a wonderful, oversized, numbered, limited edition large box set (2 VHSs). Right: a nice illustrated dj hardcover book was included in the box.

The other features were numerous and impressive in the inimitable Turner Entertainment style.

Left: The supplement video was an eye-opener as were the press kit visuals (right).

1942: The follow-up RKO film was based on the nostalgic 1918 novel by Booth Tarkington about a mid-western American family dynasty’s fall from aristocracy to working class. Welles narrated, wrote, and directed very sympathetically toward the family. Joseph Cotten, his close Mercury days buddy, plays the lead in this one and a personal friend in Kane. The deep focus cinematography of the first two films was the first time this had been done for aesthetic purposes in Hollywood film. Bernard Herrmann’s atmospheric music added to the overall feel of the first two Welles films.

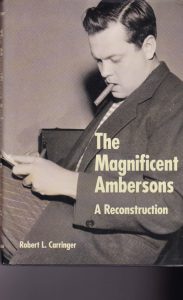

Unfortunately, the film was taken out of Welles’ hands when he was out of the country and finished by editor/soon-to-be-director Robert Wise. Key scenes were cut and re-shot hastily to get the film out. Even though it was liked by critics, audiences of the day did not warm to this classic. Left: The movie script and missing edits have been faithfully restored in Carringer’s book. There are only stills of the missing scenes; no footage was saved in the RKO vaults. Right: The book has often been written about and was on many top 10 lists from the ’40s to the early ’60s.

1941: Welles went to Brazil to shoot an interesting 3-part film, but RKO pulled the plug because of run-up costs (and his problems finishing Ambersons from South America) and so It’s All True was never released until 1993 on VHS for the first time. Welles showed a great empathetic interest in the ordinary people there, their country, and stories which make this film unique. But his RKO days were now over and he would have to act steadily to win approval to direct a movie again.

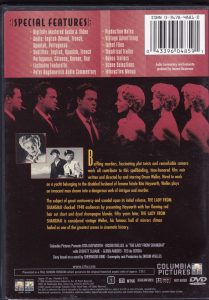

1948: Welles made a memorable movie again, acting in, directing, writing, and producing this off-beat tale of corruption. The unusual film concludes with one of the most famous scenes in Hollywood history (echoing Kane’s mirror hall scene): the hall of mirrors shootout in a San Francisco waterfront fun park. (Woody Allen famously spoofed it in his humorous Manhattan Murder Mystery.)

1948: He acted in, directed, adapted, and produced a three week shoot of Macbeth in bizarre costumes on a strange single set.

1951: Directed by Carol Reed, the charismatic Welles co-starred with Cotten again in this effective, successful adaptation of a Graham Greene post-war novel set in crumbling Vienna. Everything about this movie keeps revolving around the mysterious supposedly-dead man, Harry Lime, who doesn’t appear until midway through the movie in one of the most memorable, dramatic entrances of all time in film. He also wrote his own cuckoo clock speech with Cotten in the Great Wheel scene, and, in the conclusion, he is hunted down like a pathetic rat in the dark city sewers. Welles became world-famous for this role and he received special treatment everywhere he travelled for some time after.

No way out.

Left: The source. a small pictorial paperback. Right: The artistry of the film has led to many film criticism books.

The unforgettable Harry Lime music played by a zither player found in a cafe during the shooting.

Only the instrumental version was played in the film and wherever Welles went in Europe after the film came out to dine, restaurant musical groups would play this theme.

1951: His next movie was also shot in Europe and took 3 years to complete because of financing problems and actors’ other commitments. Welles again starred in, adapted, directed, and produced this play, and even improvised the costumes when they didn’t arrive on time. He also shot a scene in a Turkish bath when a set was not available and dubbed in missing actors’ voices. As this import DVD suggests, Welles’ work was not readily available for a long time and only gradually have cleaned-up versions of several films been restored and made available.

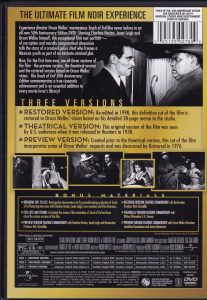

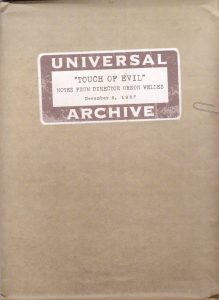

1958: A masterpiece of sordid corruption with Welles looking gargantuan and wasted as lawman Hank Quinlan. He also directed and wrote the screenplay. Fortunately, this oddity has been re-released in 3 versions and there is an enclosed envelope of Welles’ notes on what he wanted in the finished film. Welles was lucky to have some inspired casting with Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, Dennis Weaver as a weird motel clerk, Mercedes McCambridge as a campy motorcycle gang-leader, a pathetic Akim Tamiroff as Uncle Joe, and Marlene Dietrich as Quinlan’s old smug lover.

1962: It was a hard act to follow Touch of Evil, but Welles went back to Paris and succeeded with his strongly visual adaptation of Kafka’s classic novel. He cast Anthony Perkins at the peak of his Psycho fame as K. and used a massive deserted train station and its rooms for his memorable sets. This haunting film opens with Albinoni’s emotional “Adagio” and an animated scene of the parable Kafka used in his original book–later in the film, it is told, significantly, in full.

1965: Welles then directed and starred as Shakespeare’s drunken wastrel-mischief-maker pal of Henry V in this award-winning film. He also adapted the Henry V plays into a starring vehicle for Falstaff . The costumes Welles did (he was also a fine artist, often painting and sketching as revealed in the recent documentary The Eyes of Orson Welles) and the sets he used in this atmospheric black-and-white film are likewise remarkable.

Acting paid many a bill for Welles, financing his films too, and he starred or was featured in many films over the years including Jane Eyre (1944), The Stranger (1941), Black Magic (1941), Moby Dick (1956), The Long, Hot Summer (1958), Compulsion (1959), The V.I.Ps (1963), Is Paris Burning? (1966), A Man for All Seasons (1966) as Cardinal Wolsey, and Treasure Island (1972). He was, incidentally, the famous Shadow on radio.

He did many film narration jobs like the above.

We are fortunate that his entertaining, highly informative interviews are preserved in books like these.

Director Peter Bogdanovich also sat down many times with him to discuss his films.

These are the sorts of basic overview books available on Welles’ movies. The content is quite different in both the above (left: 1970 ; right: 1990).

Left: Many film critics have written about his cinema. Right: And he has been much-honored as in this 1975 AFI booklet done on the third worthy recipient of this award. There is also an out-of-print video of this celebration which features Welles hustling the Hollywood crowd for money to finish The Other Side of the Wind. In 1971, he also received an honorary Oscar for his work.

This is a recommended recent DVD about Welles’ life and career.